Lorenzo Ramaciotti, A Man, A Style

- Marco Visani

- 3 days ago

- 5 min read

From the early 1970s to 2005 at Pininfarina—where he served for 17 years as Managing Director—Lorenzo Ramaciotti concluded his brilliant career as Head of Style for the FCA Group brands. This is the portrait of an engineer with a classical education and a profoundly global vision of automotive design—not merely in geographic terms. From prototypes to mass production, from one-offs to popular models, his philosophy of automotive form and design has shaped decades of Italian and international car culture.

Words Marco Visani

Photography Leonardo Perugini

Video Andrea Ruggeri

Archive photo courtesy of the Lorenzo Ramaciotti Archive

He never says “I did,” “I designed,” or “I came up with it.”

What strikes you most when speaking with Lorenzo Ramaciotti is how rarely he uses the first person. He never says “I did,” “I designed,” or “I came up with it.” And yet he could—given the hundreds of ideas and creations drawn from his hat over a long career, first as a designer and later as head of styling.

[click to watch the video]

Designing cars is a profession that easily feeds the ego: watered daily, it can grow luxuriant, inviting admiration—especially self-admiration. With Ramaciotti, instead, this was one of the least narcissistic conversations imaginable with someone whose résumé is so formidable. Even when he picks up one of the self-published volumes collecting memories from his long working life, he deflects praise:

“It’s just a printed notebook. I didn’t have such an adventurous life to justify anything more.”

Perhaps because, had it been up to him, Lorenzo Ramaciotti would not even have become a car designer.

As a teenager, he had one ambition only: to do any job that would keep him close to automobiles. When he completed his classical high-school diploma in 1967, the only realistic option was mechanical engineering. Automotive engineering as we know it today did not yet exist, nor did modern design schools. Like many of his generation—raised on bread and Quattroruote magazine—he passed dull literature classes sketching car profiles in the margins of textbooks. We all shared that now-romantic idea that the automobile was the ultimate material aspiration: perhaps second only to housing, but far more attainable.

That emotional foundation, grafted onto a rigorous technical education, shaped the engineer Ramaciotti into a rational thinker with a wide-angle view of both his own work and that of others—grounded in realism and immune to vanity. His character also reflects a dual “citizenship”:

Emilian by birth—born in Modena, in the heart of Italy’s Motor Valley—and Turinese by adoption, having moved to Turin to study at the Politecnico.

He never left. Even today, in retirement, he lives in the hills overlooking the city. Emilian warmth and creativity blend with Piedmontese logic, courtesy, and restraint—ingredients that seem hard to reconcile, yet yield extraordinary results when properly combined.

Ramaciotti’s first paid job after graduating was at Pininfarina—the first to respond to his CV. He would stay there for almost his entire career, rising to Managing Director and Head of Styling from 1988 to 2005.

Then came the call from Sergio Marchionne and a leap into a different but adjacent world: Director of Design for all FCA brands. Few designers have worked across such extremes—from Ferrari and Maserati to Fiat. Fewer still can claim both the Ferrari 456 and the Fiat Panda among their credits. Yet “designing” is reductive: Ramaciotti’s true role was directing those who designed—conducting an orchestra rather than holding the pencil.

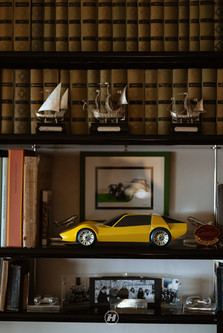

Even before that first job, there was a prologue. As a student, he entered the Grifo d’Oro competition launched by Nuccio Bertone. He presented a GT coupé model—still in his studio today. Seen sixty years later, its modernity is striking: taut lines, balanced curves, and low-profile tyres well ahead of their time. A clear sign of precocious talent.

Design entered his life almost by chance.

His true automotive idol was Colin Chapman—the man who made Lotus fast by making it light. Italy, he thought, focused too much on engines; Britain mastered handling. Why not do the same at home? That early international outlook would later define his career, even as his “less is more” philosophy found expression in exterior form—the first driver of desire in a car.

At Pininfarina, Ramaciotti worked primarily with elite manufacturers and niche vehicles rather than mass-market dynamics.

He directed the design of ten Ferraris, beginning with the Mythos concept of 1989, unveiled in Tokyo—a strategic move to assert Italian relevance in a design landscape increasingly dominated by Japan. The same logic guided projects like the Honda Argento Vivo of 1995, with its bold use of contrasting materials.

Every car has its logic.

The Peugeot 406 Coupé, for example, was born from manufacturing necessity, yet became an icon thanks to its elegance—enhanced by Ramaciotti’s insistence on preserving its proportions. This ability to maintain a strong, recognisable identity across countless designers is the Pininfarina miracle, sustained by just three heads of styling in over fifty years.

Ramaciotti cites Touring Superleggera, Bertone, Giugiaro, and independent masters such as Mario Revelli de Beaumont, Franco Scaglione, and Giovanni Michelotti as pillars of Italian design.

On the role of clients, he is clear: designers are not independent artists.

True originality emerges not from isolation, but from dialogue—preferably with clients who love cars without believing they know better.

Design today? He rejects claims that all modern cars look alike, noting an unprecedented diversity of styles.

His eternal muse remains the Ferrari 250 SWB, alongside legends like the Alfa Romeo 8C 2900 and Bugatti Type 57 SC Atlantic. Above all, two figures shaped his professional life: Sergio Pininfarina and Sergio Marchionne—very different men, united by vision and relentless work ethic.

Before Marchionne’s arrival, Ramaciotti fulfilled a lifelong dream: designing a Maserati. His Quattroporte V became the official car of President Carlo Azeglio Ciampi. Later came its successor and the Ghibli. As for Turin’s decline as an automotive capital, Ramaciotti offers no nostalgia: history moves forward, guided by reason, not sentiment.

On AI, his view is measured: artificial intelligence can recombine existing forms efficiently, but true originality—for now—remains human. For how long, he does not yet know.

About the author, Marco Visani.

Born in Imola in 1967, he has been a journalist since 1986. After beginning his career as a reporter for Il Resto del Carlino and other local newspapers, he has been writing about automobiles since 1992. He has worked with magazines such as Quattroruote, Ruoteclassiche, TopGear, Youngtimer, Auto Italiana, Auto, AM, Sprint, InterAutoNews, and EpocAuto; with TG2 television; the portal Veloce.it; and with the English publisher Redwood Publishing, active in the field of customer magazines. He is currently the Italian correspondent for the French classic-car magazine Gazoline, editor-in-chief of the bimonthly ZeroA, and contributor to L’automobileclassica, Youngclassic, Quadrifoglio, and Tutto Porsche. He also manages heritage communication for Volvo Car Italia. His writings have appeared in Corriere dello Sport-Stadio, Avvenire, Tecnologie Meccaniche, Rétroviseur (France), and Top Auto (Spain). He has published and co-authored several books for Giorgio Nada Editore and other publishers from 2016.