Cesare Fiorio, the Art of Management

- Alessandro Barteletti

- Oct 27, 2023

- 12 min read

Updated: Nov 9, 2023

As Sporting Director, he won eighteen world titles, and trained least three hundred drivers, many of whom were Italian and many discovered personally by him. He is the man who created the Lancia rally legend, almost managed to bring Ayrton Senna to Ferrari and still today holds the Atlantic crossing record. He agreed to tell his story to us in his farmhouse in Puglia, where he retired twenty years ago

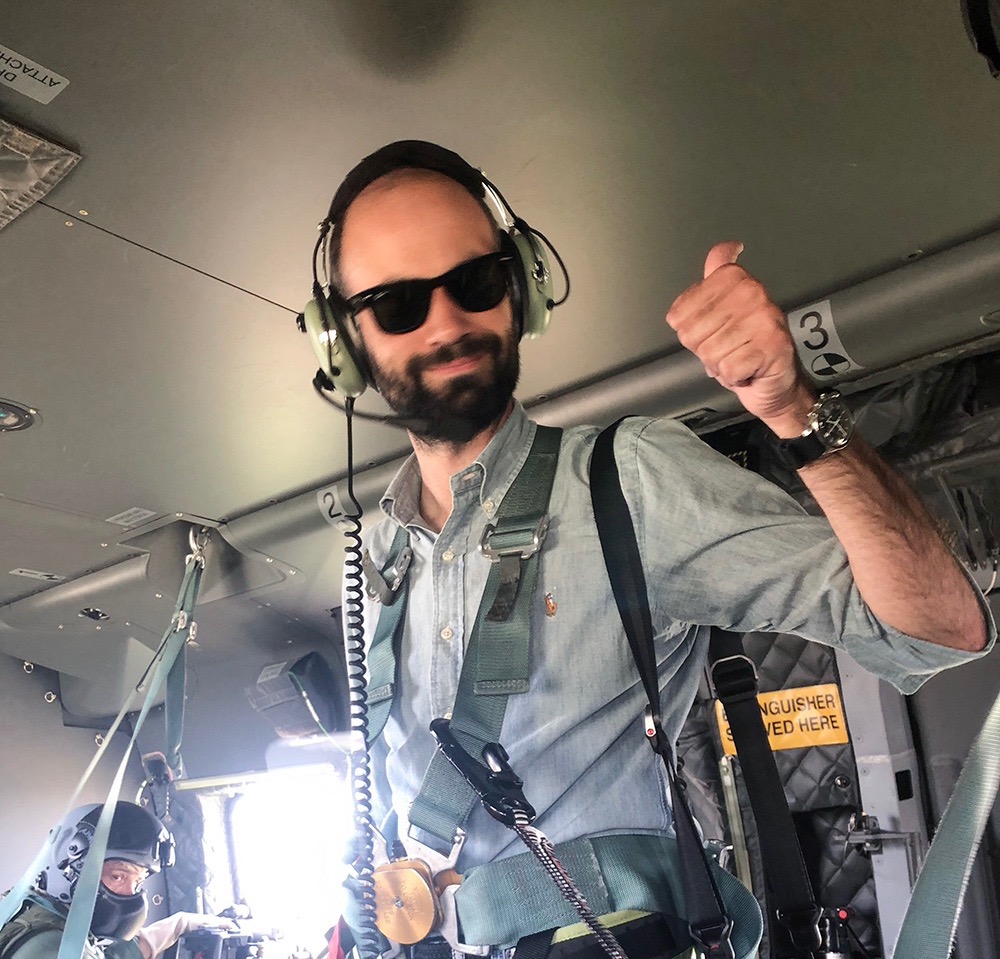

Words & Photography by Alessandro Barteletti (IG: @alessandrobarteletti)

Video by Andrea Ruggeri (IG: @andrearuggeri.it)

As soon as you arrive, the scene is far from what you might expect. Cesare Fiorio is waiting for us at the door of his farmhouse in Puglia, surrounded by dogs that fill you with joy just looking at them. “They’re all strays,” he explains, “they came here of their own initiative, and we adopted them all.” Their names each tell a story: one of them, Virus, is a black Breton who turned up on the doorstep one day during the pandemic. Class of 1939, born in Turin, Fiorio retired here a couple of decades ago. “It all happened when I stopped working on the races, something I had been doing for forty years. One day some friends took me to Puglia. I’d never been here before, and I never left after that: it wasn’t just the place I liked, but the people, their friendliness and hospitality.”

After shaking hands, Fiorio accompanies us into what he called the Breakfast Room, but which in fact is more of a museum packed with the memorabilia of a unique and unrepeatable life. He calls it that because this is where guests are served breakfast, all strictly home-made, including the ingredients: Masseria Camarda in Ceglie Messapica is an ‘agriturismo’ but also a farm. We sit beneath what was once the bodywork of the Formula 1 Ferrari in which Nigel Mansell won the Brazilian Grand Prix in 1989, on Fiorio’s début as Sporting Director in Maranello. An extraordinary story, told also by the many photos, trophies and other mementoes around us.

[click to watch the video]

All things considered, as Lancia and Fiat rally director, Cesare Fiorio won 18 world titles. Looking back over those amazing years, you realise that his greatest achievement was to be able to compete on equal terms with adversaries of the calibre of Porsche and Audi, even when the terms were actually far from equal. Behind this were creativity, improvisation as well as the ability to invent techniques and strategies. And this is what we came to talk about, the Fiorio Method.

Racing is part of the Fiorio family DNA: that goes for you, your son Alex, as well as your father Sandro, who raced successfully in a few competitions (including the ‘Mille Miglia’) before getting a job with the Pesenti family’s Lancia. And going with your father to the races, you also met some of the greatest champions of that time. Who was that young Cesare, and what were his dreams and ambitions?

I remember Gigi Villoresi, Alberto Ascari… I was very young at the time, and they were very famous. More than meet them, I saw them close-up, but it was enough to make me realise that my own goal was to race cars. Things were different back then, you couldn’t race until you were eighteen, when you could get a driving licence. That was when I began competition racing, and managed to win the Italian GT Championship in 1961 behind the wheel of a Lancia Appia Zagato.

That was when you discovered your true vocation: organisational, or as they say today, managerial skills.

As I racing driver, I realised that something was always missing. I said: if this thing had been there, or if someone had been there in charge of doing that other thing… it really didn't take much to get better results. And so I began to organise races for others, and that became my speciality.

In 1963, with Dante Marengo and Luciano Massoni, you set up something that went on to become the Lancia racing team, today a piece of car racing history: the HF Squadra Corse. What was the intuition behind that success?

At the time there was a club you could only join if you had owned at least six Lancia cars. It was called Lancia Hi-Fi, high fidelity, expressing the members’ bond with the brand. I took these two initials - HF - and put them into a racing team. There were three of us at the start, then we took on two mechanics, Luigino Podda and Luigi Gotta. Then Lancia gave us a small - very small - shed, with no equipment, no rooms, not even a hoist. We had the cars prepared externally, by Facetti in Bresso or Bosato in Turin, and we just managed the maintenance. But in our own small way we did things well, and one step at a time we grew and began racing with the cars we had prepared.

Few resources, great determination: aside from the race reports, there are many interesting behind-the-scenes episodes. Can you tell us about the first time you met Roger Penske in Daytona?

It was 1968, and we decided to race a Fulvia Zagato at the 24 Hours of Daytona. It was our first time in America, and we were facing opponents of the calibre of Porsche, Chevrolet… I remember I arrived three days before the race, trying to get a feel of the place and understand how things worked. One of the things I realised was that the pit position was very important, given the importance and delicacy of the stops in such a long race. I chose mine and told the organisers, who didn't bat an eyelid. A couple of days later, Roger Penske arrived. To be honest I didn't know who he was, but in the States he was already a big name and his team was one of the favourites in the race. He went to the organisers, and they told him that his usual pit had already been taken by Lancia. He came over to me, introduced himself and told me that it was his pit. I answered, “Look, the organisation gave it to us, we’ve already settled in and we’re not going to move now.” His gentle manners became more hostile, and I can still remember the sarcasm in his voice when he looked at our little Fulvia: “Who do you think you are!” But I didn’t budge. In the end he walked off, sending us to hell, and we kept the pit.

At the height of the Fulvia’s successes, after winning the RAC in 1969 (another incredible story: the bushing taken off Lampinen’s car to allow Källström’s to get going again and win), Fiat bought Lancia and you were sent packing. And then you met Gianni Agnelli…

When Fiat took over the ownership of Lancia, the changes were instant. I was called in by the Personnel Manager who told me they didn't need me anymore. Lancia belonged to Fiat, and Fiat would do the job instead of me: “You’ve got three months to find yourself another job, after that our relationship will come to an end.” So I went to the Turin Motor Show, where all the stars of this world met every year, hoping to find a few good contacts. As I was doing the rounds, I noticed a line of frantic photographers and journalists: behind them was Gianni Agnelli. I didn’t know him personally at the time, but he saw me and recognised me. “Fiorio,” he said, “now you can help us win a bit too!” I looked at him, puzzled, and told him that I would have loved to if his Fiat hadn't just fired me. A week later, the Personnel Manager called me: “You can stay, we would like you to run both the Lancia and the Fiat racing teams.”

Let’s talk about the Lancia Stratos: a puzzle-like project, where you managed to put all the pieces together even when it wasn't sure they would fit.

I had a very clear idea about what the car should have been like: Bertone supplied the bodywork, we worked on the chassis, Dallara was going to develop the suspensions after that. The problem was the engine. Fiat and Lancia didn't have anything suitable, so one day I took a big risk and went to see Enzo Ferrari in Maranello. He showed great respect for our work, because - as he underlined - we managed to win with very few resources available. I told him about the new project we were working on, describing it as something futuristic that however was missing the most important part: the engine. “My Dino will be perfect on your car,” he said. A one in a million event. And the rest is history.

And then, once again, Fiat put a spoke in the wheel: at the height of the Stratos period, the managers in Turin preferred to invest in the 131 Abarth version, with an eye on the commercial returns of the operation. You didn’t lose heart, and turned this umpteenth “incident” into another success story. Then came the Group Bs, and with the rear-wheel drive 037 the world title was yours, to the detriment of Audi and its four-wheel drive.

Audi was ruling the world at that time, being the first to introduce four-wheel drives and having gained experience with that technology that we still didn’t have so weren’t familiar with. I knew that our only chance was to build a completely different car from theirs, closer to our own traditions. That’s how the 037 was born: lightweight, a central rear engine and great handling. Surrounded by a team of tireless mechanics, brilliant engineers, great designers and top drivers. A combination that, in 1983, helped us to win, beating the deadly and, until then, unbeaten Audi Quattros.

Do you remember any episodes in particular from that time?

We had just finished a special stage on a dirt road and we were in the lead. All the teams were lined up along the same road for assistance. The Germans were a few metres ahead of us, but at one point I saw an Audi pull up at full speed and stop in front of us. Their manager got out, panting, and without saying or asking anything threw himself under one of our 037s. He thought he would find out something, but of course we were compliant, there were no hidden secrets under the car. This episode really struck me, as it proved that our ability to react had caught them off-guard.

The Group B years were crazy: cars were monsters, and drivers were tamers, not to mention the fans, who literally tried to hug the cars as they flew past in the race, sometimes even touching them. What was it like to be part of that era?

There were many, too many accidents, both among the public and the crews. Losing Attilio Bettega in Corsica in 1985 and Henri Toivonen and Sergio Cresto again in Corsica in 1986, we were also victims of this. It was inevitable that something had to change. I remember when, at the height of the 1986 season, the Federation put an end to Group B, saying that from the following year our cars wouldn’t have been allowed to race. The regulation stated at least two years’ notice, but that was an extraordinary situation. I accepted the decision, even though I knew we didn't have anything ready. The new Group A only accepted cars that were mass-produced with at least 5000 every year. All we could do was look at the cars that were already in our catalogues, and so the choice fell on the Lancia Delta 4WD. A few months later, at the début Rally in Montecarlo for the first race in the Championship, we took a new win home, with Miki Biasion in first place with Tiziano Siviero and Juha Kankkunen with Juha Piironen in second.

In spring 1989 the call came from Ferrari, when - we have to admit - Ferrari was a disaster.

I was at the Portugal Rally, it was Saturday and we were winning, when I got a completely unexpected phone call. It was Cesare Romiti, the then-Chairman of the whole Fiat Group, and wanted me to come home for a chat. I tried to explain that we were in the middle of a race, but he wouldn’t listen. I left instructions for the team and on Sunday morning I took the first flight from Lisbon to Milan, where Romiti was waiting for me. “We need you at Ferrari, are you on board?” Of course, I told me, without hesitation, explaining that I could have been ready in a few weeks. “You don’t understand, we need you right now,” he said. So the next day I went off to Maranello and that’s how my adventure with Ferrari began.

Many years before that, you had already worked at Maranello.

That was in 1972, when Enzo Ferrari called me to manage his team for the Targa Florio. “I think you can be of help to us in Sicily,” he said. He thought that the Sicilian race - at that time a very important part of the prestigious Sport Prototypes championship - was closer to a rally in management terms. I agreed, and we won the race with Arturo Merzario and Sandro Munari’s Ferrari 312 PB.

In the first Formula 1 season you won three races, the first on your début, as many as Maranello had won in the three previous years. And in 1990 with Alain Prost you just missed the world title. You revolutionised the whole thing, right from the beginning demanding that the design – at that time decentralised to the UK under the management of John Barnard - should return home.

It couldn’t work, a series of dynamics had been triggered that for me were unacceptable: when things went well it was thanks to the UK, when things went bad it was Maranello’s fault. I asked Barnard to move to Italy, but he refused so we said goodbye.

Is it true that you then asked Giampaolo Dallara to become Technical Director? Looking for someone to replace Barnard, I wondered who was the best, and of course I contacted Dallara, also because of the experiences I had had with him in the past. We had known each other since the Stratos period, and I had put him in charge of the development of all the Lancia cars for the track speed races, from the Beta Montecarlo Turbo to the LC1 and LC2. But Giampaolo was very busy with his company, and thought that accepting Ferrari’s offer would have been a kind of betrayal to his employees who had always believed in him. Seeing where he got today, I think he made the right choice.

You also tried to steal Ayrton Senna from McLaren and bring him to Ferrari.

It wasn’t hard to see that Ayrton Senna was the man to focus on. In 1990 we already had Prost and Mansell in the team, two brilliant drivers, but bringing Senna to Maranello meant that he would no longer be an opponent. I was really struck by the way Ayrton managed the whole negotiation. Discussing his contract, who his engineers would be, which driver he would be with on the team and all those aspects that have to be clarified in the draft contract, it was just me and him, no manager, no lawyers. We reached an agreement, but then Ferrari put the pressure on and this blew up the whole operation, and ultimately led to the end of my relationship with Maranello. History, and Ayrton’s own history, could have taken a completely different turn.

Tell us about your son Alex: what does it mean to be a driver’s dad? My son’s only defect is that he’s called Fiorio. When he started to make his name, it was clear that the kid had talent, and this made me aware of a very difficult situation. It would have been natural to take him on for his skill, but that would have fuelled a whole load of criticism that would have clouded his career. So I made the ethically most correct choice, even though I knew he was a really good driver and deserved better, in fact he won not only the Group N World Championship with a private car, but in 1989, aged just 24, he came second behind Miki Biasion with a Jolly Club car. Today, Alex lives in Puglia like me, and he also runs the Fiorio Cup, a competition held on a track we built behind the farm.

Cesare Fiorio maritime pilot: your adventure with the Destriero is still an unbeaten record. I raced motorboats for eighteen years. Any Sunday when I wasn’t busy with the teams, I would race in the sea, and I must admit I won many of the most important races in this category, including two world titles. But I had my heart set on the Blue Ribbon, the prize awarded to those crossing the North Atlantic, from Europe to America and back again, in the shortest possible time. My first attempt was with an Azimut Benetti boat, but one of the engines broke and we dropped out. I had another chance right after I stopped working at Ferrari, when I received a phone call from His Majesty the Aga Khan, who offered me the possibility to manage, organise and lead that extraordinary boat, the Destriero. It was really futuristic: built by Fincantieri, it was over 67 metres long and was driven by three General Electric aeronautical turbines, the ones installed on the famous F-117 Stealth bomber. We set off on 9 August 1992 from the Ambrose Light in New York, covering 3106 nautical miles without refuelling on the Atlantic Ocean, as far as the Bishop Rock lighthouse in the Scilly Isles in England in 58 hours, 34 minutes and 50 seconds, with an average speed of 53.09 knots (almost 100 km/h). Yes, the record still hasn’t been beaten.

So your life has been dominated by passion. But there’s still one thing we haven't talked about: music. Music is another of my great loves. I have played most instruments, from the drums to the double bass. At one point I even had a jazz band, where I played the saxophone and Enrico Rava the trumpet. But then he became a famous artist and my fate led me elsewhere.

--

Alessandro Barteletti is a photographer and journalist. Through his photos, he has been revealing the reality behind news stories, as well as social and sports events, for almost 20 years. Being keen on anything that can be driven fast, on the roads or flying in the sky, he has specialized in the auto, aviation and space industries. Among his clients: National Geographic, Dallara and Italian Air Force. Alessandro currently lives between Rome - where he was born - and Modena, the heart of Motor Valley; he is the editor-in-chief of SpeedHolics Magazine.

Comments