Peter Monteverdi, the Unstoppable Venture

- Sean Campbell

- May 1, 2025

- 22 min read

Updated: Jun 26, 2025

Only true car lovers and historians would recognize the Monteverdi badge. Perhaps even fewer would know that its creator, Peter Monteverdi—the last Swiss luxury car maker—had once been a racing car driver of some repute. While plenty of column inches cover his exploits in the design and manufacturing world, this story delves more deeply into the lesser-told, and wildly mixed, fortunes of his racing career.

Words Sean Campbell

Photography Paolo Carlini

Archive Courtesy of Monteverdi Archive - Verkehrshaus der Schweiz

Peter Monteverdi during the construction of the Monteverdi Hai 450 SS, 1969 - Photo Courtesy of Verkehrshaus der Schweiz

A kick in the backside

Imagine: it was a kick in the backside and a punch in the nose that set Peter Monteverdi on the path to automotive legend. He had been determined to study medicine when, in the mid-1940s, a particularly crabby teacher called him an idiot. In the ensuing argument, the teacher called him to the front of the class and kicked him in the behind as a form of "discipline."

Peter went home and recounted everything to his father, Rosolino, in the tractor and plant machinery workshop his father had built. Without hesitation, Rosolino rolled up his sleeves, marched straight to the school, stormed into the classroom, and punched the teacher in the nose.

After the incident, Peter’s father sent him to another school that focused more on practical skills rather than theoretical study—an environment far better suited to his skills and interests (and his attention span). It was there he met a vocational advisor, Ernst Bertschi, with whom he got along handsomely. Taking stock of Monteverdi’s adept hands and upbringing, Bertschi encouraged Peter to pursue a career as an automobile mechanic, beginning a cascade of events that would lead to one of the mid 20th centuries most loved car brands.

Italian Blood, Swiss at Heart

Peter Monteverdi grew up in Binningen, a small town near Basel. His roots traced back to Italian immigrants who had settled in Switzerland during the late 19th century, bringing with them a heritage of hard work and technical ingenuity.

His father embodied these traits, building a reputation as a skilled tractor mechanic and opening a workshop that became a cornerstone of the local community.

Peter Monteverdi in his pedal car, 1938 - Photo Courtesy of Verkehrshaus der Schweiz

As a boy, Peter spent much of his time in the workshop, immersed in the sights, sounds, and smells of grease and machinery.

Peter Monteverdi at the wheel of a Vevey Diesel - Photo Courtesy of Verkehrshaus der Schweiz

But while Rosolino's world revolved around tractors and practical engineering, Peter's imagination raced toward something entirely different—cars. Not just any cars, but fast ones.

At just 15, influenced by Bertschi, Peter left home to serve his apprenticeship at the Swiss firm Adolph Saurer near Lake Constance. Saurer was a pioneer in heavy commercial vehicle engines, and Peter’s early years were spent learning to tune automobile engines. The apprenticeship required him to spend time in the town of Arbon before moving closer to home, working at the Saurer service and repair shops in Birsfelden, near Binningen.

Peter Monteverdi for Saurer at the Basel Trade Fair in 1952 - Photo Courtesy of Verkehrshaus der Schweiz

The Monteverdi Special & Dreams of Racing

He didn’t just dream of fast cars either—he built them. At just 16 years old, he began crafting his first car, the Monteverdi Special. During his apprenticeship at Saurer, Peter had thrown himself into the mechanical craft with gusto. Despite his youth, he was often chosen to tackle complex mechanical problems. One day, while riding his moped to work, Peter spotted a battered Fiat Tipo 508C Balilla 1100 in the yard of a dealership. It had collided with a tree, but on closer inspection, Peter decided it was still in decent working order. Knowing the Balilla was highly tunable, he saw an opportunity to restore and transform it into his first performance car. Remarkably, Peter was only 17 and not yet old enough to drive himself.

His ultimate ambition, however, was to become a professional racing driver. After a few trade-ins, steadily getting better cars each time, he possessed something raceworthy, the Alfa Romeo 1900 Sedan—at that time a popular touring car.

And so his racing career began in earnest. In his view, mechanicing was now just a means to fund his racing career. Monteverdi drove bravely and boldly, but was a rookie in comparison to the seasoned, cool competition he faced. He was, for want of a better phrase, too keen. Able to drive well, able to gather great speed, but with little consistency. He went through car after car, flogging each to its end. His competitors did however, learn to take him seriously. They had seen a natural talent in him that in time could be molded and honed and developed. In an outdated VW convertible, he even managed to finish 3rd in the hill climb at Reigoldswil in 1954, beating a 4.5l Talbot in the process.

In 1955, he bought a one year old Porsche 356 1500 S. Small, fast and agile, it was perfect for hill climbs. And so, going all in as was his wont, he entered every single hill climb event in the 1955 season. The car did well but struggled against Porsche’s own specialized models, which the company itself entered in the season to dominate the 1.5l category and grow its brand in the Swiss market. Undeterred, Monteverdi decided that he would try again in 1956, after converting his own engine to a 1.3l to race a category below where he would stand a better chance. An impossible task to most, this was too easy for the autodidactic skills he’d built over his teenage years.

Through Tragedy, From Tractors to Sports Cars

Before the season began though, tragedy hit the Monteverdi family. Rosolino had taken suddenly ill. A malignant brain tumor was diagnosed, and before the week was out, he was dead. Peter, just 22, realized the family’s fate now rested on his shoulders. He essentially had no choice but to take over the family business, which Rosolino had nurtured from simple shed to respectable, modern—and large workshop. This came with a cost. It needed to be paid for, mortgage payments, upkeep, day-to-day business. While the garage ticked over in trade, the family was cash poor. This was the Monteverdi family’s only true asset of wealth.

Young Monteverdi weighed up his options, and took the workshop in his own direction—moving from repairing tractors and machinery to tuning sports and luxury cars. A clean slate, the beginning of a legacy.

The business got off to a promising start, with word of mouth spreading about the Garage Monteverdi. Before long, the country’s first true sports car owners —for the industry in Switzerland was still in its infancy–were bringing their cars to him. With the business up and running, Peter turned his attention back to hill climbs. In his mind, a reputation as a racer would only help his business’ reputation, while of course the young man would be continuing his true ambitions of becoming a star of the racing world.

The restored Monteverdi Garage on Oberwilerstrasse in Binningen, 1957 - Photo Courtesy of Verkehrshaus der Schweiz

As he had planned, the now 1.3l Porsche more than held its own fighting a weight class down. A 5th place finish at the Steinholtz hill climb showed promise—and finally a 1st place at Kandersteg was the crowning moment. Young Monteverdi was getting noticed. A feature in Automobil Revue magazine put him on the map. Pausing for thought to weigh up the next step, he decided one simple thing—he would need a faster car.

Falling for Ferrari

He drove to a Chrysler dealership in Bern having gotten wind of a very special car being traded in. He left his Porsche there that day and drove home in a Ferrari. A 1953 3L Mille Miglia Coupe. He was still just 22 years old. Indeed, he was almost laughed out of the dealership when he asked about the car, until they saw his Porsche and decided to take him a little more seriously.

Monteverdi knew he was taking a risk. The Ferrari was not in top condition—the clutch was harsh and it bellowed blue fumes, but he was captivated. It was arguably the first illogical, purely romantic decision of his life (aside from his desire to race cars). He’d traded in a perfectly reliable and high-performing Porsche for a temperamental Ferrari. On a mountain pass from Bern to his home near Basel, one of the two distributors that powered the 2 banks of 6 cylinders broke. He drove home on six cylinders, and proudly took his mother for a drive in his new Ferrari before getting started on repairs.

Bold Ambitions & Opening Gambits

Peter Monteverdi with his Ferrari 3-Litre Mille Miglia - Photo Courtesy of Verkehrshaus der Schweiz

The Ferrari would cause headache after headache, but never true heartache. It was a labor of love. Indeed, it was a mechanical problem that led to a moment that would define Monteverdi’s career. Defective Ferraris, after all, need new parts. And parts need to be distributed. Switzerland had just a single Ferrari agent in Bern.

Peter Monteverdi racing his Ferrari Mille Miglia in Rheinfelden, 1956 - Photo Courtesy of Verkehrshaus der Schweiz

After hauling the car back across the french border following an ill-fated tour to Paris and a busted valve under the Champs-Elysee, he dissected the car, and removed the damaged piston. Knowing full well that the future would bring the need for many more repairs and spare parts, the bold young man wrapped the piston up, placed it in the back of the car, started it up and made for Maranello—the home of Ferrari. “Why not go right to the source?” he reasoned. And while there, why not pitch the idea of his Binningen workshop becoming Switzerland's newest Ferrari dealership?

He was confident that if they could excuse his age and just hear him talk shop—technical features, specs, granular details—and of course see him in the Ferrari that he himself owned, they would at least hear him out.

Piston in hand, the earnest young man addressed the security guard, and pleaded his case. The next morning, he was meeting Signor Gardini, Head of Sales at Ferrari. Gardini presented him with every spare part he’d requested, and even better, took him on a tour of the works at Maranello.

And so began a careful game of cat and mouse. Even the bold young man knew that he couldn’t blithely ask for a franchise as a Ferrari dealer in Binningen. And so he played his opening gambit. Could he buy a sports racing car? Indeed he could, was the response. A brand new Second Series, 4 cylinder, 2 liter Testa Rossa Roadster was just about to arrive.

And if he were to buy it, he enquired, what chance would there be of attaining a franchise in Switzerland? The response was cryptic but not impossible to follow—without buying the car, there's no chance of the dealership. Here he was, on the cusp of owning not just a sports racing Ferrari, but owning the preeminent Ferrari dealership in an entire country at the age of 22. Indeed, were he to succeed, he would become the world’s youngest Ferrari dealer.

Finding A Way

The obstacle in his path, however, was the 43,000 Swiss Francs he’d been informed as the price for the Testa Rossa. Monteverdi drove home with plenty to ponder, and a problem to puzzle over.

He needed to make more money. He needed to spend more money to make that. And the more he invested, the less he would have, and the smaller the chance of becoming a Ferrari dealer (and Testa Rossa owner). Impressive as the tuning shop was, it could only fit two cars. And as impressive as Monteverdi’s skill was, he could only work so many hours. So, he decided to kill two birds with one stone. He would scale up the garage, hire help, and while he was at it, he’d buy the damn Testa Rossa. It’d just take some bending of the truth to do it.

In his discussion with the bank for a loan to expand the garage, he tacked on a few extra tens of thousands of Swiss Francs. With the business turning over nicely, the bank paid out, and in the autumn of 1956, work began. By winter he would have a modern, six car garage, complete with electrical power tools. The little tractor workshop had come some way, and Monteverdi had gone some way to funding the purchase of the Testa Rossa.

During the renovations, he made a number of trips to the Modena test track to meet Gardini. Somewhere between a test drive for the would be customer, and a test of the would be dealer, these meetings held incredible importance. Ferrari were not willing to let Monteverdi represent their brand if he proved unfit to handle their cars. And so, under the guise of taking both the Testa Rossa and the bigger, more powerful—and more tempestuous— 3 liter, 4 cylinder Monza, Gardini secretly appraised the young Swiss man’s skill behind the wheel.

Before the year was done, Monteverdi made another trip to Modena, still in his Mille Miglia GT coupe, to iron out any finer points in his dealership pitch. When he left that day, a deal had been struck. For his purchase of the Testa Rossa, he would not only own a Ferrari dealership, he would own the distributorship for the entire county of Switzerland (save for the existing Bern dealership). He sold the Mille Miglia, purchased the Testa Rossa, made sure to spend an extra few days testing it on the track (he did, after all, still harbor ambitions to race) and so began a new chapter of Automobil MONTEVERDI.

A Racer Is Born

In April 1957, Monteverdi obtained his racing license in quite some style. With three new white stripes added to the Testa Rossa, the car stood out from the crowd as truly Swiss amidst an international glut of would-be racers at the Monza circuit during an FIA-affiliated race driver’s course. Monteverdi’s fervour had seen him register for the course before anyone else, and so the car also sported the number 1.

Peter Monteverdi and his mechanic, ready to race the Ferrari Testa Rossa, 1957 - Photo Courtesy of Verkehrshaus der Schweiz

With his freshly obtained license, and having impressed none other than Karl King during the course, Monteverdi now dreamed of being a Ferrari works driver. But the higher powers would need some convincing. He elected to give the 1957 season his best, and see how far it might take him. Meanwhile, he also had the not small task of getting his new business off the ground. A Ferrari dealership had to sell Ferraris after all. He started wisely, offering a brand new 250 GT to an old racing colleague at cost price. Then a few weeks later, he sold his first at list price. Once again, the young man showed he was the master of the opening gambit…

But these aims ran parallel to one another in Monteverdi’s mind, just as they had years before. The more he raced, and won, in his Testa Rossa, the more demand would grow, and the more customers he would have.

Ups, Downs & Ups

At the end of April, he shocked onlookers as he qualified in second place at a race in Aspern, Vienna. On race day, he flew into an early lead, the Testa Rossa broadsiding wildly all over the track as it roared from the starting line. As before, Monteverdi’s racing was the opposite of his mechanical skill—all heart and guts, with a deficiency of composure. He was soon overtaken by the renowned Willy-Peter Daetwyler. Not to be put off, Monteverdi floored the Testa Rossa and became embroiled in a 4 way battle for pole position. Daetwyler ahead, two more Testa Rossas breathing down his neck. In the heat of the dogfight, Monteverdi spun off the track, before coming to a stop facing 180 degrees in the wrong direction.

With no damage done, and adrenaline pumping, he rejoined the race and little by little, pulled himself back into 4th position, where he would finish. Not a bad return to the track. It may not have been the result he wanted, but it came with all the thrills that seduce race car drivers into the life in the first place.

Months later, Monteverdi faced stiffer competition at the Belgium and Spa-Francorchamps, with a number of full-time professional drivers, including Tony Brooks and Colin Chapman, joining the ranks. The qualifying laps were a bitter pill to swallow–he could not keep up no matter how he tried. When the starting flag fell and the real race began, he quickly found himself completely alone, his rivals disappearing into the distance.

No longer in a fight for position, Monteverdi felt a strange freedom. He was free to focus on technique and skill, to just enjoy the ride and make it out alive. Still only 23, Monteverdi had lost close friends to racing, and it dawned on him that he was but a mistake away from meeting his end at all times. Guts and heart could get him pretty far, but they could also get him killed.

And so over the remaining laps, he set himself a new goal—not to win but to get better, race more smoothly, and simply try to finish within visible distance of the leading group. This newfound serenity began to pay out right away. Within just a few laps he’d not only gained ground… having glided past car after car, calculated in his movements and consistent in his technique, he’d driven himself back into second place!

With victory in sight, his blood and thunder instincts kicked back in, albeit tempered, and so began the hunt. Then inexplicably, while cresting a hill at 160 kmh, the front windshield collapsed and flew off the car, leaving the exposed driver battling the full force of the wind. Just like in Aspern, the car spun off track, landing in a ditch. But as luck would have it, he at least settled in the ditch facing in the right direction this time. Undeterred by the wind, he went back to work, back to that balancing act of cold-blooded technique and fire-in-the-belly determination. In a race filled with reputed professional drivers, he finished in fourth place.

With his self belief validated, Monteverdi committed to the rest of the season with full force (within financial and work-bound reason), even driving at Nürburgring 1000 km in May, with Karl Foitek.

The following week, he took his momentum to new heights at the slalom in Campione.

His first race that would count towards the Swiss Championship, the tight, windy obstacle course would take more finesse than speed. This would be all driver-skill, no engine output. Not to mention, the weather was wet and slippery, and Willy-Peter Daetwyler was back in town. But there was no need to fret. Monteverdi raced the perfect race, and finished first by a distance—three seconds ahead of Daetwyler.

The Monza Upgrade & The Racing Addiction

A burgeoning reputation led to a boom in business. Monteverdi was living his dream. But the competition in racing was fierce, and only getting tougher. Not only was Daetwyler on his list of rivals, so too was a certain Heinrich “Heini” Walter, a fearsome Porsche driver from Monteverdi’s own stomping ground, Basel Land. If he was going to be Swiss Champion, he was going to have to win a lot of hill climbs. But that required power. The 2l Testa Rossa was an elite car, but it didn’t have the power to keep up with Daetwyler’s 3l Monza. So he simply decided to buy one himself.

With Ferrari having recently displaced the Monza at the head of its arsenal with a 3 liter V12 Testa Rossa, Monteverdi went on the hunt for a used Monza at good value for money. He found just that in Geneva—a 1955 model of the 750 Monza— but not before sending the Testa Rossa off in style with a 6th place finish at the international hill climb in Schauinsland in the German Black Forest.

On the 1st of August, with a full tank of fuel and a lot less money in his pocket, Monteverdi drove his new Monza home from Geneva, and started preparing for the 1958 season.

It wouldn’t be unreasonable to assume that the obstinate Monteverdi was as unyielding as ever in his goal of being the Swiss racing champion. Nothing in his life thus far would suggest a swaying of emotion, or any fear or doubt. But in truth, he was beginning to wonder if his racing ambitions were no more than a pipe dream. He could justify his racing by saying it brought him new customers. But for every race, he and his mechanic at Automobil MONTEVERDI would close up and disappear for a week at a time, killing any potential profit.

And then there was the creeping fear of meeting a swift and horrible end. Before every race, waiting for the flag to drop, he confessed to wondering if he’d even make it out alive. Then the race would begin, the engine would roar, the smell of burning rubber and hot oil would envelope his senses, and he’d dive once more into the breach. In short, he was addicted. And who could possibly blame him.

The Danger of Temptation

And as any addict can attest to, there’s nothing quite like temptation. Still enthused by the notion of being a member of the Ferrari works team, he travelled again to Modena to test drive a new 750 Monza—one of the last ever—which was in its final stages of completion. Having not even tested his own Monza on the track, Monteverdi hopped in the new one and, to everyone’s shock, set times equal to the team’s best drivers. Impressed by his marked improvement, Gardini offered that there may be an opening for a reserve driver, but it was slim. And if he were going to drive a car like that again, he’d need to own a car like that. But price wise, it was out of the question.

Over the next few months, Monteverdi determined to impress the Ferrari higher-ups with his skill alone, and focused on getting results in hill climbs.

His efforts proved disastrous. At Gaisberg in August—known for its tight hairpin turns—he elected to drive his Monza instead of the more nimble Testa Rossa he still owned. His confidence that he could handle its weight well enough to reap the rewards of its power was grossly misplaced, and he finished well behind Daetwyler.

Constantly committed to improvement, Monteverdi stuck at it, learning to keep the Monza under control at wild speeds, and clocking better and better times. At a hill climb in The Grisons, he even managed a 5th place finish, in the company of Daetwyler, Hans Herrmann, and the famous Wolfgang von Trips.

The Crashes, The Booms & The Rejections

Alas, accidents and hurt are just about inevitable for anyone who pushes themselves and their cars to the brink, and while he had thus far evaded tragedy, he would soon have more than one brush with it. In September 1957, at the hill climb of Martigny-La Forclaz, he clipped a photographer standing beyond the safe zone, right in his driving line. Somehow, the photographer emerged relatively unscathed bar a few sprains and bumps, while Monteverdi got away with a damaged knee and bloody face. The Monza, a badly damaged side. Then in Alsace, the hastily repaired Monza suffered a steering loss in a hairpin turn and flew off the wet track. He was dragged from the cockpit, unable to move at all. Paralyzed completely, he demanded to be checked out of the local hospital and taken home to Basel. On a stretcher in the back of his mechanic’s Citroen DS 19, he made his way back home to be diagnosed with a broken pelvis.

While he healed up, he focused on business, electing to renovate and upscale his garage once again, selling the Testa Rossa to part fund the operation.

In 1958, Monteverdi made another trip to Maranello, this time with hopes of fulfilling his lifelong dream of being named on the team. After building a respectable racing reputation and proving his skills, not to mention his exploits in the Monza, he thought his moment had arrived. But the answer from Signor Gardini was a polite but firm "no." Gardini explained, “I have attended too many funerals of good friends who have driven for us.” While this seemed like a concern for Monteverdi’s safety, the truth likely had more to do with business. Ferrari couldn’t afford to lose their only dealer in Switzerland. For Monteverdi, this was a crushing blow. The dream he had worked tirelessly toward was now out of reach.

Still, Monteverdi resolved to continue racing privately. But with money tied up in his expanding garage business and the sale of his Testa Rossa to fund renovations, he decided to also sell his Monza. Unfortunately, the Monza was already on the brink of being outdated. With Ferrari introducing a 3-liter Monza V12, buyers were unlikely to invest in the older 4-cylinder model. Monteverdi, however, had other plans for the car.

A Glorious & Unexpected Return

Rather than sell the Monza as it was, Monteverdi transformed it into one of the world’s fastest GT cars. With the help of Dr. Alfred Hopf, who had purchased Monteverdi’s Mille Miglia GT Coupe earlier, he created the Ferrari-Monteverdi 750 GT. The Monza received a brand-new steel body, complete with gullwing doors, and an array of features to make it suitable for road use. These included a quieter, more road-friendly exhaust system, a handbrake, power brake systems, and even a heating and ventilation system.

The 750 GT’s debut coincided with a significant personal milestone for Monteverdi. At Ferrari’s annual press conference in Modena, Enzo Ferrari himself awarded Monteverdi a medal for being the best private Ferrari driver of the year. It was an ironic twist, considering Monteverdi had attended the event reluctantly, knowing it would focus on Ferrari’s racing plans—plans that no longer included him.

Peter Monteverdi receives the golden Ferrari lapel badge in Modena, 1957 - Photo Courtesy of Verkehrshaus der Schweiz

Monteverdi’s return to racing wasn’t limited to hill climbs and GT events. He made his debut in single-seater racing, piloting a Cooper-Norton F3 at the Ollon-Villars hill climb, where he finished third. To cap it all off, he claimed victory at the Mitholz-Kandersteg hill climb in his own Ferrari-Monteverdi 750 GT.

Peter Monteverdi racing the 750 GT at the Mitholz – Kandersteg hill climb, 1958 - Photo Courtesy of Verkehrshaus der Schweiz

Back to Business

Despite his racing successes, Monteverdi began to face challenges in his business. Ferrari’s decision to sign direct contracts with Swiss dealerships effectively ended Monteverdi’s monopoly as the sole importer. No longer the exclusive Ferrari distributor in Switzerland, he had to rethink his strategy. Racing had become a financial drain, and Monteverdi decided to sit out the following season to focus on expanding his garage and building a stronger business foundation.

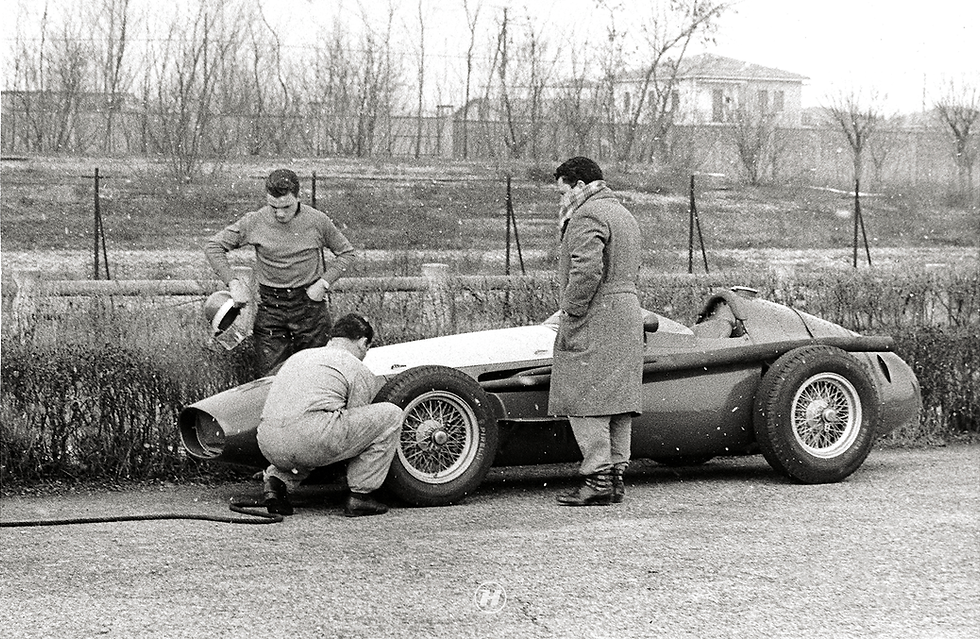

Monteverdi didn’t abandon racing entirely. He experimented with other cars, including a Maserati 750 and even test drove a Formula 1 Maserati under the watchful eye of Guerino Bertocchi, Maserati’s chief mechanic. During the test drive, Monteverdi pushed the car so hard that the driveshaft sheared, tearing a hole in the car’s body!

Peter Monteverdi with the Maserati Grand Prix 250 F in Modena, 1959 - Photo Courtesy of Verkehrshaus der Schweiz

And on his 25th birthday, he celebrated by competing again in the Nürburgring 1000km race, partnering with Karl Stangl in a Mercedes-Benz 300 SL. The duo finished third in their category, further cementing Monteverdi’s reputation as a versatile and skilled driver.

Peter Monteverdi at the start of the 1000 km race Nürburgring, 1959 - Photo Courtesy of Verkehrshaus der Schweiz

The Birth of MBM

Monteverdi’s racing ambitions took a new turn with the demise of his Ferrari relationship, and the subsequent creation of MBM. Interestingly, the name would have three meanings over the years; Monteverdi Basel Mantzel, then Monteverdi Basel Mitter (after Gehrard Mitter, his next partner), and finally, after going it alone— Monteverdi Basel Motoren).

His goal was to design and build single-seaters that could compete in Formula Junior and Formula 3 categories. In partnership with ingenious mechanic Albrecht-Wolf Mansel, MBM Sport emerged as a dedicated racing arm, producing lightweight, high-performance cars powered by engines from DKW.

Peter Monteverdi in a DKW Formula Junior at the Schauinsland hill climb, 1959 - Photo Courtesy of Verkehrshaus der Schweiz

Monteverdi himself raced these cars, achieving respectable results in hill climbs and circuit events, even finishing in second place (behind rival Heini Walter) at the slalom in Dübendorf.

Later models, once Monteverdi had parted ways with Mansel, were powered by Ford Anglia, OSCA, and in the case of the MBM Formula 1, Porsche. It was in this MBM Formula 1 that Monteverdi made his one and only F1 Grand Prix appearance—at Solitude race course near Stuttgart. It lasted two laps before a defective clutch forced his retirement.

Peter Monteverdi and the MBM Formel 1 in Monza, 1961 - Photo Courtesy of Verkehrshaus der Schweiz

From Racer to Manufacturer

As Monteverdi’s racing career began to wind down, his focus shifted toward manufacturing road cars. In 1964, he’d become the official Swiss sales representative for BMW, in turn ceding the licenses to sell Lancia, Jensen, Rolls-Royce, and Bentley that he’d won in the years prior. Between BMW and Ferrari, business was booming. But it wasn’t enough to scratch the creative itch. He hadn’t built a car in more than three years, and an idea for a new MBM GT was beginning to consume him. In 1965, he received the perfect motivation to bring the idea to reality. A directive from Ferrari informed all Swiss dealers that they were expected not just to hit better sales numbers, but from here on out, pay in advance for spare parts, and deal with a newly appointed Swiss sales rep in Geneva. It only took ten days for Monteverdi to make his move. He decided to go it alone.

And so began the chapter of his life that’s best documented. In 1967, he introduced the 375 series, a line of luxury GT cars that combined Italian styling with American powertrains. Collaborations with renowned designers such as Pietro Frua and Fissore resulted in striking designs that appealed to wealthy clientele.

The launch of the 375 S Frua - Photo Courtesy of Verkehrshaus der Schweiz

The 375L and 375S models featured powerful Chrysler V8 engines, luxurious interiors, and exceptional performance, establishing Monteverdi as a serious player in the luxury car market.

The Hai 450 SS, introduced in 1970, was another bold statement from Monteverdi. This mid-engine GT car featured aggressive styling and a 7-liter Chrysler V8, making it one of the fastest cars of its time. While production numbers were limited, the Hai cemented Monteverdi’s reputation as a builder of exclusive, high-performance automobiles—a legacy still appreciated today by true SpeedHolics, if not widely recognized by the general public.

Monteverdi Hai 450 GTS 1973 - Photo Courtesy of Verkehrshaus der Schweiz

Onyx Formula 1, The Death of Peter Monteverdi & A Lasting Legacy

No mid-late 20th century automotive visionary's story would be complete without a foray into Formula 1. Monteverdi’s came in 1989, when he acquired the Onyx Grand Prix team along with his old friend and partner Karl Foitek, just over 30 years after they’d raced the Nürburgring 1000km. While the venture was short-lived, ending the following season, the team did achieve a notable 3rd place finish in the Portuguese Grand Prix, with the Swede Stefan Johansson behind the wheel.

The Team Onyx Monteverdi Formel 1 - Photo Courtesy of Verkehrshaus der Schweiz

Monteverdi lived fast, and while he didn’t die particularly young, he wasn’t old when his time came. He was 64 when he passed away from cancer. His final days were spent not in a hospital bed, but in the apartment above his workshop in Binningen. He had come full circle.

Today, his legacy lives on through his cars and his contributions to Swiss automotive history. The Verkehrshaus der Schweiz (Swiss Museum of Transport) in Lucerne houses a collection of Monteverdi’s creations, ensuring that his story continues to inspire future generations of car enthusiasts.

Peter Monteverdi was more than a racer or a manufacturer. He was somewhere between prize fighter, mad scientist, and cunning strategist—a man who dared to dream big and pursued those dreams with relentless determination. As a racer, he was hot blooded. As an engineer, a problem-solving, highly imaginative visionary, and as a businessman, a cool and calculated strategist —with that passion bubbling just under the surface, fuelling his every move.

From his humble beginnings in Binningen, through his never-say-die spirit as a race car driver, to his status as the last Swiss luxury carmaker, Monteverdi’s journey is a testament to perseverance, ingenuity, and the power of a father who would punch a bully in the face for his son.

--

SpeedHolics would like to thank the Verkehrshaus of Lucerne (the Swiss Museum of Transport) for making available the two cars featured in this article. The Monteverdi High Speed 375L (chassis no. 3126) was later reacquired by Monteverdi and repainted. The 375/4 (chassis no. 2059), on the other hand, has always remained the property of the company. The steering wheel is part of the specific configuration originally requested by Peter for this particular car. Each vehicle was, in fact, built according to the specifications provided by the customer, demonstrating that individuality was very important to Monteverdi.

Comments